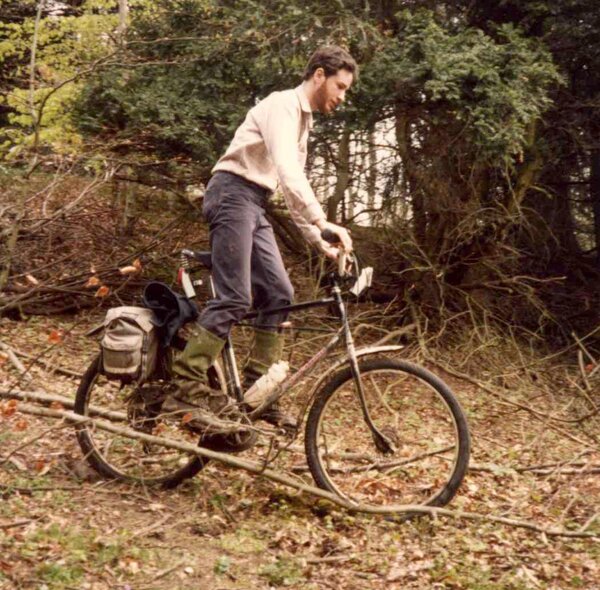

1979 and all that

Let's get one thing out of the way; aerodynamics.

The problems associated with cutting through air only begin to come into play at above 12mph.

Above that speed and the effect is relatively small, but it increses exponentially. I thought about for how much of any one ride would I be travelling in excess of 12mph.

Even if I were out for an adrenalin hit, those periods didn't amount to much in time, mostly because I was travelling fast, it would be all over quite soon.

Then would come the decidedly below 12mph (vis climbing the next hill) period, which would take a long time. I also found that I would regret the speed that a downhill (especially a nadgery one) would pass, and I began to relish them more by travelling relatively slowly.

Therefore, aerodynamics play no part whatsoever in my design concepts, and I never waste any time at all worrying about it.

You are very perceptive to make reference to the standing position of trials riders, this is indeed a prerequiste of my designs. Just think about Graeme Obree's bike for a moment. He was quite able to get a racing tuck with his high handlebar up against his chest.

I realised early on that when riding off-road, one needs to be able to throw your body weight way forward, and way back, as well as from side to side.

If you're all stretched-out, there's no further to go, whereas if you're riding position is quite short, you have plenty of flexibility to manoeuvre.

A phrase kicked about a lot in the early days, and it is not without substance, is the concept of man and machine working as one entity. This is exemplified in the extreme in track racing, road racing etcetera, where the rider does not move very much in relation to their bicycle.

It could be considered a fundemental in traditional bicycle design and, in general, that concept runs through practically every bicycle produced, to some degree or another.

It is a concept I reject completely ~ the focus of my designs is to minimise this idea of rider and bike working together; as far as possible, the frame design and layout should allow both entities to work quite separately (but not completely, although that does happen from time to time), more like a co-operative relationship, if you take my meaning.

Now we come to your mention of the S word.

Stability.

This is influenced by three factors: Centre of mass and steering geometry, followed by weight bias for off-road bicycles.

And I've said enough for the time being, so I'm going to sign off.

I'll continue with the next exciting instalment of this thrilling tale discussing the part those three factors play in my designs.

Are you asleep yet?

Let's get one thing out of the way; aerodynamics.

The problems associated with cutting through air only begin to come into play at above 12mph.

Above that speed and the effect is relatively small, but it increses exponentially. I thought about for how much of any one ride would I be travelling in excess of 12mph.

Even if I were out for an adrenalin hit, those periods didn't amount to much in time, mostly because I was travelling fast, it would be all over quite soon.

Then would come the decidedly below 12mph (vis climbing the next hill) period, which would take a long time. I also found that I would regret the speed that a downhill (especially a nadgery one) would pass, and I began to relish them more by travelling relatively slowly.

Therefore, aerodynamics play no part whatsoever in my design concepts, and I never waste any time at all worrying about it.

You are very perceptive to make reference to the standing position of trials riders, this is indeed a prerequiste of my designs. Just think about Graeme Obree's bike for a moment. He was quite able to get a racing tuck with his high handlebar up against his chest.

I realised early on that when riding off-road, one needs to be able to throw your body weight way forward, and way back, as well as from side to side.

If you're all stretched-out, there's no further to go, whereas if you're riding position is quite short, you have plenty of flexibility to manoeuvre.

A phrase kicked about a lot in the early days, and it is not without substance, is the concept of man and machine working as one entity. This is exemplified in the extreme in track racing, road racing etcetera, where the rider does not move very much in relation to their bicycle.

It could be considered a fundemental in traditional bicycle design and, in general, that concept runs through practically every bicycle produced, to some degree or another.

It is a concept I reject completely ~ the focus of my designs is to minimise this idea of rider and bike working together; as far as possible, the frame design and layout should allow both entities to work quite separately (but not completely, although that does happen from time to time), more like a co-operative relationship, if you take my meaning.

Now we come to your mention of the S word.

Stability.

This is influenced by three factors: Centre of mass and steering geometry, followed by weight bias for off-road bicycles.

And I've said enough for the time being, so I'm going to sign off.

I'll continue with the next exciting instalment of this thrilling tale discussing the part those three factors play in my designs.

Are you asleep yet?